by Scott Roney

“This is it?”

“That’s all we have.”

I was incredulous. This girl was about to become our daughter, and the little information we had in her file, was not very accurate.

“But she had ringworm, right? That’s why her head was shaved,” insisted Sarah.

“Ahh… there’s nothing about that on here,” the physician replied with an Ethiopian lilt, trying her best to sound professional despite the fact that she didn’t know any more than we did.

“And we were told that her mother was in the area – was known in the area.”

“She was abandoned. We don’t know anything about her mother.” Her voice was more certain now, despite the conflicting information we had received the previous month.

I flipped through the few pages of documents again, the way you search a drawer one last time for something you already know isn’t there. It wasn’t the doctors fault, or anyone’s fault for that matter. There were no records. No one knew. Here in Ethiopia, there simply were no answers.

After we brought Jalayna home, the same questions lingered 2 months later. When was she abandoned? Why? Where was she born? What were her parents like? Were her parents dead or dying, or destitute? Why was she in the orphanage for so long? If she was brought there as an infant, why was she only referred to us at more than 2 years of age? Was she always in the same orphanage?

Her first 3 months home were an exhausting blur. I remember very little – other than Sarah passing out next to me each night with scarcely 10 minutes of conversation after enduring a day of tantrums and failed communication. Our lives had finally reached a pseudo-normalcy when, at Jalayna’s 6-month checkup, another question was added.

Why wasn’t she growing?

Children adopted from orphanages usually eat voraciously and gain weight rapidly as they recover from the effects of malnutrition. We were warned that she might hoard food in response to years to scarcity. When we told social workers and physicians that we couldn’t get our daughter to eat, they were utterly stumped.

We finally discovered that Jalayna had been born without a thyroid. The only reason she had grown as much as she had – and she was still small and underweight – was the residual hormone received through her birthmother in the womb. Either way, she had been metabolically running on fumes since birth, and it was only because of her birthmother that she made it this far.

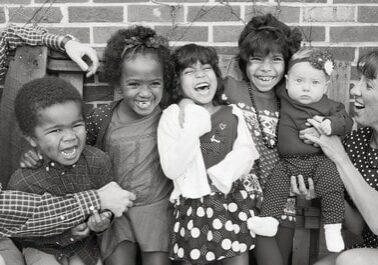

Had she remained in Ethiopia, she would have never grown any more. Her body would have gone into puberty before she was old enough for kindergarten, then her brain would have shut down, and she would have spent her life in a near-vegetative state with a 20-pound body. Now she takes a readily-available replacement hormone, loves going to school, and makes a new friend everywhere she goes.

But we still don’t know what we will say if she asks about her first parents, or asks anything about her past. It’s frustrating that we cannot know any more about the first 2 years of her life.

But there was one more thing we learned that day in Addis Ababa.

“The cross around her neck – what does this mean?” Sarah asked.

“Oh,” the physician smiled, “that means she has been baptized.”

We were awestruck. By whom? When? Where? It didn’t really matter though. At that moment, she was “sealed by the Holy Spirit … and marked as Christ’s own forever” (BCP). Long before she became part of our family, she was part of God’s family. Until she had an earthly father, her Heavenly Father was doing exactly what He said that He does (Psalm 68:5), no matter where she was.

And in that moment, we learned all that we truly needed to know.